Ending the national eviction will have a different impact in different states, with some positive outcomes, like an increase in homes available for rent or for sale and dire ones like increased homelessness. Getting rental assistance payments out to tenants at risk of eviction is critical, especially in states like South Carolina, which halted most evictions during the pandemic but doled out little rental assistance.

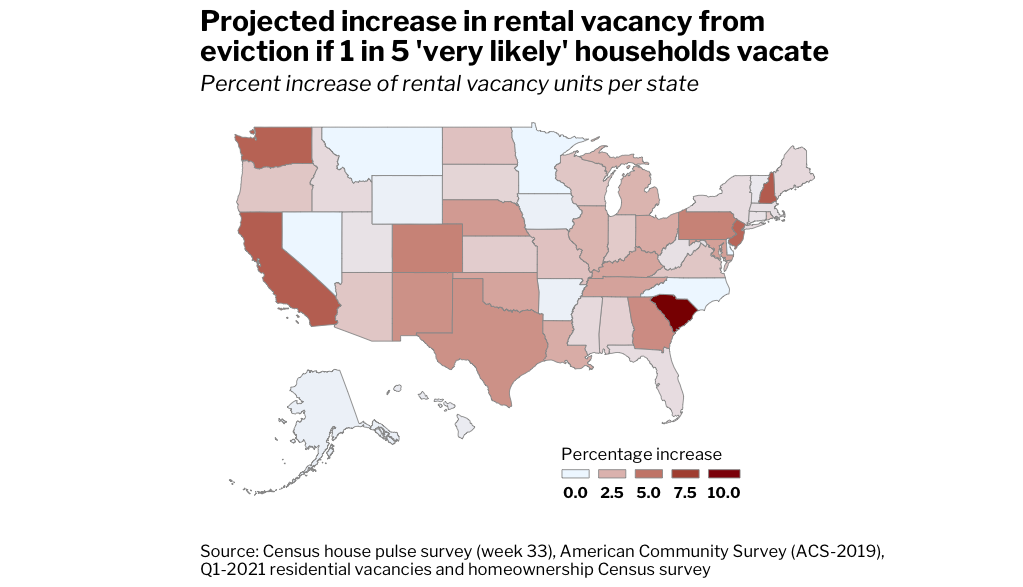

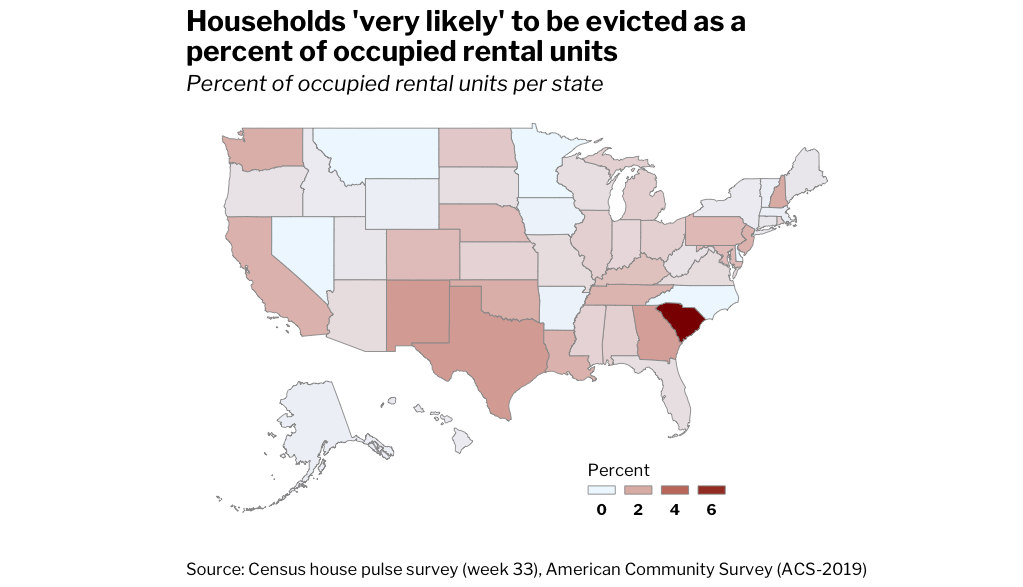

States with a large number of renters at risk of eviction and very few vacant homes for rent could see the biggest disruptions to their housing markets. If one in five renter households who reported they are “very likely” to be evicted had to vacate their homes, South Carolina, New Hampshire, California, Washington and New Jersey would all see a more than 5% increase in vacant rental units when the moratorium ends. That could increase the supply of homes for rent and homes for sale, which could weigh down rent and home price growth.

States like Pennsylvania, which halted most evictions while successfully getting rental assistance to tenants, could see a more than 4% rise in rental vacancies. And, although Idaho and other states that continued evictions throughout the pandemic will likely see little to no impact from the moratorium ending, renters in those states can still benefit from renters’ assistance. This is according to an analysis of the Census House Pulse Survey and the American Community Survey.

During the pandemic, the CDC issued an eviction moratorium and the Treasury made over $46 billion in funding available to households unable to pay rent or utilities. However, evictions continued in some parts of the country as some states did not give additional guidance on how the eviction moratorium should be enforced, and some did not successfully set up infrastructure to distribute rental assistance.

“We tried to use the eviction moratorium in court, but judges often didn’t accept it,” said Ali Rabe, Idaho State Senator and Executive Director of the eviction prevention non-profit Jesse Tree. “The wording of the eviction moratorium was vague and up to the interpretation of judges. We have been going to eviction court every week, and we only successfully implemented the eviction moratorium one time, but unfortunately that person still ended up evicted.”

South Carolina has the largest share of renters at risk of eviction

South Carolina has the largest share of renter households who say they are very likely to face eviction at 7.3%. If just one in five of those households had to leave their homes, the number of vacant rental units would increase by 10.2%. That would be a large enough increase in available rental supply to weigh down rents substantially. However, it would also mean that over 8,000 households would be evicted and potentially face homelessness in a state with a current homeless population of around 4,000.

The eviction moratorium was briefly enforced in South Carolina when the State Supreme Court postponed most evictions in March 2020 until May 2020. Since then, whether or not evictions proceeded was up to the county court. For example, in Charleston, evictions completely stopped in April 2020, but then resumed at about 40% of pre-pandemic levels.

In South Carolina, evictions can happen quickly, but rent relief has not made it to the vast majority of renters in need. In South Carolina, a landlord may file for eviction just five days after a missed payment if the rental agreement does not stipulate a notice period. That gives tenants almost no time to apply for and receive rental assistance. To make matters worse, although the state received $272 million from the federal government for rental assistance, less than $100,000 of the money had been distributed as of the end of June.

Without the eviction moratorium, tenants will have to hope their landlord is willing to wait for them to apply for and receive rental assistance. But in many parts of South Carolina, rents and home values have risen substantially, and landlords will often prefer to evict in order to find a tenant who will pay a market rent. For example, in Myrtle Beach, rents have increased 21% since last year and home prices have increased 18%. A more than 10% increase in rental vacancies could translate to more homes available for rent or for sale, but the households evicted would also have to find a new place to live, which would be very difficult with an eviction on their record.

Pennsylvania may see an uneven increase in evictions

In Pennsylvania, the share of renter households reporting that they are very likely to face eviction is 1.6%, which is close to the national rate of 1.2%. If just one in five of the renter households reporting that they are very likely to be evicted had to leave their homes, it would increase the number of vacant rental units by 4.4%. That could be a large enough increase in available rental supply to depress rents.

Across Pennsylvania, the way courts have handled eviction proceedings has varied widely because, similar to South Carolina, there was no state-level guidance on how the eviction moratorium should be upheld. As a result, some judges halted evictions entirely, and some allowed evictions in certain cases.

Philadelphia’s approach wisely prioritized getting renters’ assistance to avoid eviction. Landlords are required to go through the Eviction Diversion Program before seeking a court eviction for nonpayment of rent until the end of August. This mandate means that tenants and landlords must first go through mediation instead of criminal proceedings to resolve their issues. As part of the mediation, landlords and tenants are assigned a counselor who may help the tenant apply for Pennsylvania’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program to avoid eviction.

“With so much rental assistance funding still available, it would be a grave public policy error if tenants are still evicted given that the majority of eviction filings are for non-payment of rent,” said Phyllis Chamberlain, Executive Director of Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania. “Non-profits and local governments are outreaching to tenants and landlords to ensure that rental assistance gets out the door as quickly as possible. Thankfully, the U.S. Congress provided significant rental assistance funding with very few restrictions and the Pennsylvania General Assembly did not impose additional restrictions. Restrictions equals less funding out the door less quickly.”

Evictions will not rise in Idaho

In Idaho, the share of renter households reporting that they are very likely to face eviction is only 0.3%. In Idaho, the evictions continued throughout the pandemic– there were the same number of evictions before the pandemic began as there were when the pandemic was in full effect. Therefore, Idaho will likely not see any meaningful increase in evictions or rental vacancies when the CDC eviction moratorium ends.

Part of the reason that evictions continued in Idaho during the pandemic was because renters were evicted before they could access rental assistance. “Tenants knew about the moratorium, but they didn’t know how to assert it,” said Rabe. “There were forms that needed to be filled out and filed, and just filing the form with the court costs $160. That is a lot of money to someone who can’t afford rent. On top of that, most of the rental assistance isn’t getting out because governments don’t have the community approach. People in eviction are in crisis, they may not have internet, they may not understand the process, or they need someone to help them.”

It’s not too late to get renters’ assistance

Connecting renters at risk of eviction with renters’ assistance can still prevent evictions from occurring. Texas, for example, has successfully distributed more than $500 million in rental assistance to more than 80,000 households.

“Texas initially had difficulties rolling out their rental assistance programs because the infrastructure had to be built county by county,” said Dana Karni, Managing Attorney at Lone Star Legal Aid. “What moved the needle was an online portal administered by the state and building a coalition of eviction defenders through the Eviction Right to Counsel Project, whereby anyone facing eviction can get legal help. We helped tenants complete applications for rental assistance, we helped landlords get information as well. Now the government is funding our efforts, so that is a stamp of approval for our work.”

The eviction moratoriums have to end at some point; otherwise landlords will sell their properties to avoid dealing with tenants who do not pay rent. That may be good news to households looking for a home to buy or rent at an affordable price. However, we can lessen the devastation to renters financially hurt by the pandemic by getting rental assistance out before eviction procedures begin. If you know of a neighbor, friend or family member who has missed rental payments during the pandemic, you could volunteer your time by helping them apply for rental assistance, or you could donate to non-profit organizations that assist renters facing evictions.

Table: Households very likely to be evicted by state

| State | Households “very likely” to be evicted | Households “very likely” to be evicted as a percent of occupied rental units | Vacant housing units for rent (projected Q1-2021) | Projected increase in rental vacancy from eviction if 1 in 5 “very likely” households vacate |

| Alabama | 6,016 | 1.0% | 73,082 | 1.3% |

| Alaska | 137 | 0.2% | 10,222 | 0.2% |

| Arizona | 6,476 | 0.7% | 59,282 | 1.7% |

| Arkansas | 517 | 0.1% | 36,337 | 0.2% |

| California | 106,921 | 1.8% | 284,115 | 6.0% |

| Colorado | 11,390 | 1.5% | 41,753 | 4.4% |

| Connecticut | 1,712 | 0.4% | 37,205 | 0.7% |

| Delaware | 0 | 0.0% | 8,840 | 0.0% |

| District of Columbia | 265 | 0.2% | 14,396 | 0.3% |

| Florida | 16,932 | 0.6% | 289,615 | 0.9% |

| Georgia | 31,082 | 2.3% | 122,927 | 4.0% |

| Hawaii | 548 | 0.3% | 20,307 | 0.4% |

| Idaho | 554 | 0.3% | 8,731 | 1.0% |

| Illinois | 17,077 | 1.0% | 112,228 | 2.4% |

| Indiana | 6,598 | 0.8% | 67,489 | 1.6% |

| Iowa | 305 | 0.1% | 28,606 | 0.2% |

| Kansas | 3,553 | 0.9% | 37,233 | 1.5% |

| Kentucky | 8,296 | 1.4% | 44,532 | 3.0% |

| Louisiana | 10,341 | 1.8% | 60,675 | 2.7% |

| Maine | 605 | 0.4% | 9,401 | 1.0% |

| Maryland | 11,215 | 1.5% | 56,003 | 3.2% |

| Massachusetts | 1,711 | 0.2% | 35,924 | 0.8% |

| Michigan | 11,517 | 1.0% | 75,630 | 2.4% |

| Minnesota | 0 | 0.0% | 35,537 | 0.0% |

| Mississippi | 3,039 | 0.9% | 48,820 | 1.0% |

| Missouri | 5,762 | 0.7% | 49,800 | 1.9% |

| Montana | 0 | 0.0% | 11,832 | 0.0% |

| Nebraska | 3,911 | 1.5% | 18,532 | 3.4% |

| Nevada | 0 | 0.0% | 46,134 | 0.0% |

| New Hampshire | 3,191 | 2.0% | 8,309 | 6.1% |

| New Jersey | 21,029 | 1.8% | 60,045 | 5.6% |

| New Mexico | 6,019 | 2.4% | 25,356 | 3.8% |

| New York | 8,810 | 0.3% | 163,391 | 0.9% |

| North Carolina | 0 | 0.0% | 113,398 | 0.0% |

| North Dakota | 1,523 | 22% | 12,646 | 1.9% |

| Ohio | 15,811 | 1.0% | 89,331 | 2.8% |

| Oklahoma | 9,550 | 1.9% | 50,783 | 3.0% |

| Oregon | 3,083 | 0.5% | 28,828 | 1.7% |

| Pennsylvania | 25,800 | 1.6% | 94,113 | 4.4% |

| Rhode Island | 1,354 | 0.9% | 13,430 | 1.6% |

| South Carolina | 43,021 | 7.3% | 67,300 | 10.2% |

| South Dakota | 722 | 0.6% | 9,597 | 1.2% |

| Tennessee | 15,318 | 1.7% | 79,591 | 3.1% |

| Texas | 91,795 | 2.4% | 384,593 | 3.8% |

| Utah | 1,177 | 0.4% | 27,491 | 0.7% |

| Vermont | 140 | 0.2% | 4,044 | 0.5% |

| Virginia | 7,791 | 0.7% | 72,167 | 1.7% |

| Washington | 20,040 | 1.9% | 55,220 | 5.8% |

| West Virginia | 865 | 0.5% | 17,180 | 0.8% |

| Wisconsin | 5,033 | 0.6% | 46,076 | 1.7% |

| Wyoming | 157 | 0.2% | 10,922 | 0.2% |

| United States | 548,710 | 1.2% | 3,179,000 | 2.8% |

Methodology

The number of households (i.e., the total population divided by the household size) very likely to be evicted are those answering “very likely” to the question from the Census House Pulse Survey, week 33: “How likely is it that your household will have to leave this home or apartment within the next two months because of eviction?” The number of renter-occupied units comes from the American Community Survey (ACS), 2019. We approximate the number of vacant housing units for rent per state in Q1-2021 by applying the national growth rate of vacant housing units (between the Q1-2021 residential vacancies and homeownership Census survey and the ACS-2019) to each state.

United States

United States Canada

Canada