This is an account I wrote as Redfin’s CEO about what it has been like to run a publicly traded company hit hard by the pandemic. It’s the first of three installments, about our dawning recognition of the pandemic.

The pendulum never stops swinging in the middle. A colleague gets a cough and within hours your offices are closed; within weeks you have almost a hundred million in unsold houses on your books and a thousand idle employees.

The company where I work, Redfin, is a technology-powered real estate broker, half Amazon, half Century 21. We started out as a website for seeing homes for sale on a map, then we hired our own real estate agents, as employees not contractors, with salaries and health-care benefits, not just commissions. Employing agents was hard to do in the up-and-down housing business; with the economy likely to open and close over the next year, it has gotten harder now.

We had more than $750 million in 2019 revenues, so we’re bigger than a coffee shop that has to close after one bad week, but not too big to fail. Before this pandemic started, we employed about 3,900 people. Over the past 60 days, we’ve scrambled to virtualize our service and sell off our risky assets. We’ve seen the government shovel money at lenders who were still too scared to lend, succeeding and then failing and then succeeding again at keeping the housing market open. We saved some jobs and lost many others.

February 18: “It Never Hurts to Be Prepared.”

I was at a family reunion in the mountains north of Seattle when an employee first asked about coronavirus, on a chat channel employees use to ask me questions:

Hi Glenn! Long time listener, first time questioner :). This month, COVID-19 has steadily been spreading globally… My question is: if COVID-19 gets a foothold in the US, do we foresee it impacting Redfin’s day-to-day operations? Do we have a strategy in the event one of our offices is exposed to it? I don’t mean to cause any panic… risk of infection in the US is extremely low and there’s a great deal of misinformation about COVID-19 floating around. But it never hurts to be prepared.

Have you ever planned a trip somewhere cold from somewhere warm? Your brain sees the temperature on a screen, but you can hardly bring your arms to pack a sweater. I felt that way reading this note: pay attention was one reaction, but it was warring with another: not a problem now.

The question came in on February 18. It took me a week to respond, in part because of my vacation, in part because we’d switched to a new chat format that I wasn’t used to checking. But I should have taken it more seriously. I responded on February 25, with platitudes about putting employees’ health first, following CDC guidelines, avoiding travel to China or Italy, notifying HR if you got sick.

March 3: “Some Trouble Breathing”

Two weeks later, on Tuesday, March 3, we decided to close all of our offices. Over the weekend, the first U.S. coronavirus death had come to light in the Seattle area, but the city was still wide open; Seattle-area schools wouldn’t close for another two weeks. New York that day confirmed its second coronavirus patient.

Demand from the just-finished weekend was roaring; people were touring homes and trying to buy them at record levels on Sunday night. Seattle’s numbers were off, but an analyst said that our agents just hadn’t had time yet to update our systems.

It wasn’t until Tuesday evening that execs got a report on what really happened: Seattle’s home-buyers had “sort of disappeared.” In 52 weekends a year across the 94 markets Redfin serves, these kinds of dips were inevitable and almost always inconsequential. But this one made us all a bit queasy.

At the insistence of our chief technology officer, Bridget Frey, we’d worked that day on a plan to run our business remotely. We agreed this was only a contingency; it was as if a prerequisite for preparing was the insistence that preparations were unnecessary. When we left the office that night, the last bits of software that had been running on computers in our office were drifting up to the cloud.

An hour later, at 7:09 p.m., I got a text from our chief product officer, Christian Taubman. Still new on the job, Christian was ordinarily quiet, but one issue he wouldn’t be quiet about was the possibility of a pandemic. His voice would be crucial in the weeks to come. His message that night was about an employee who’d gotten sick.

FYI — I forwarded you an email re **** experiencing cold/flu symptoms and some trouble breathing. Just FYI but think you should know ASAP.

I was eating dinner when I got the text message, and texted back to ask if the employee needed help getting care, and when he had been in the office. It took me only one more bite to conclude I was under-reacting, and another to realize I had been for days. I left the table to call Christian. I tried to remember if the employee had asthma, and said it was pollen season. Christian told me the employee had gone to the hospital for a test.

At 8:22 p.m., we called an executive staff meeting for 8:30, to discuss whether to close our 78 offices. No major Seattle companies had shutdown yet. We came as we were into the Google Hangout, and so it was the first time I’d seen the uncomposed background life of the people I’d worked with, sometimes for a decade. Some argued to wait until morning, to clear our heads. Others pointed out that if we disregarded health-department guidance and closed offices now, we’d also have to act as our own health department later, to decide when to re-open offices. Though many businesses have now embraced this responsibility, doing so at the time felt extreme.

But we knew that we’d been talking ourselves out of a reaction for too long, and that my delays could have already put employees at risk. Even if the employee now at the hospital didn’t have the coronavirus, someone else would go home with cold symptoms tomorrow. The state didn’t have the capacity to test each of those people, and we had no interest in making our own judgments about what was a cold or the coronavirus. A shutdown was only a matter of time.

By 9:50 that night, I’d drafted an email for the execs to review, and by 10:56 we’d emailed an announcement that all of our offices would be closing. At 11:24, we got word from the employee at the hospital that his tests showed he had only a cold, but at that point it didn’t matter anymore. The pendulum had started swinging, and we felt relieved to be doing something about it.

March 4: “A Significant Drop in Demand”

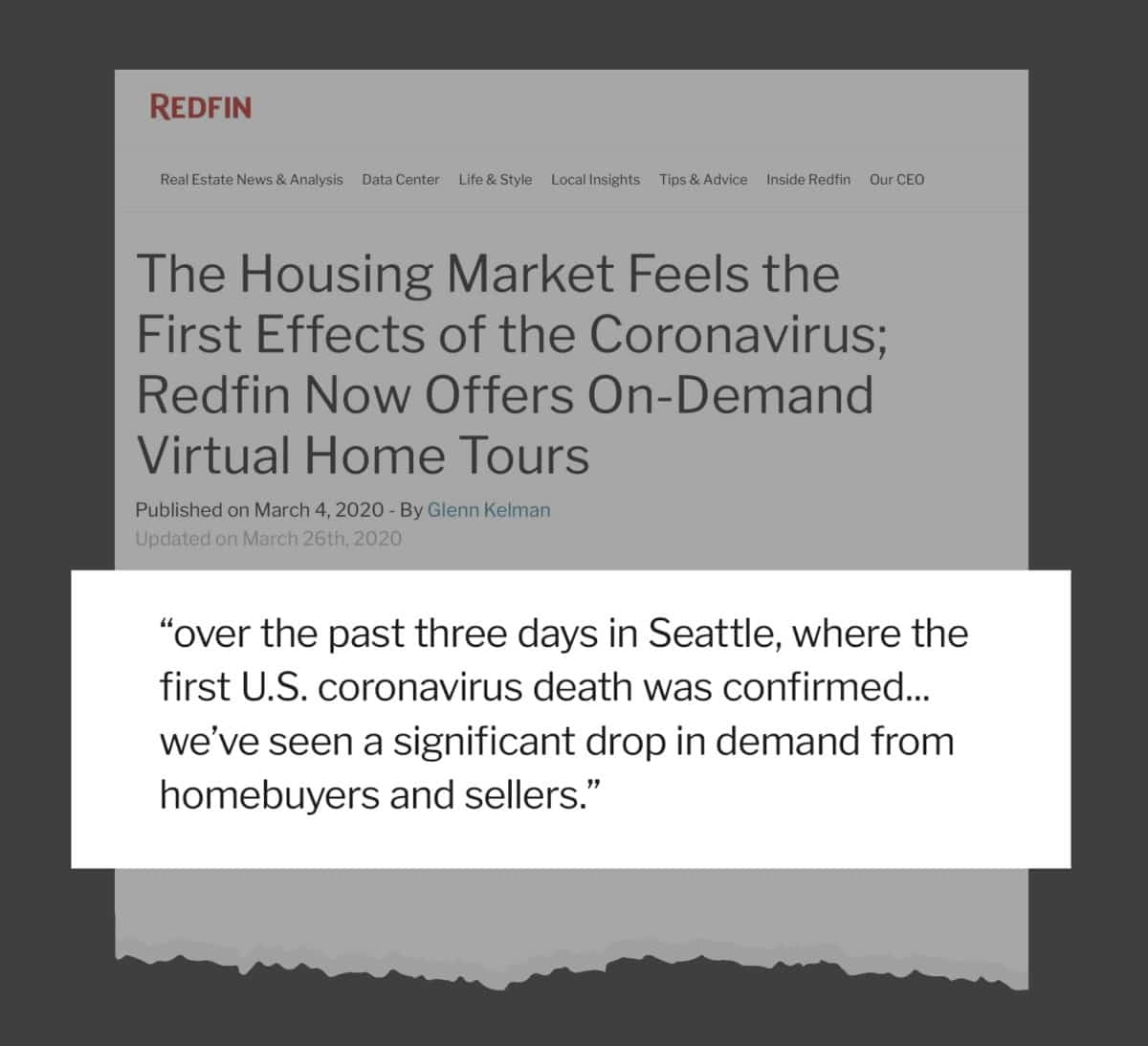

That same night, on Tuesday March 3, we decided it was time to warn our customers that Seattle’s shortfall could become a national trend. Through email campaigns, press pitches and customer meetings, our agents, economists and marketers drew thousands of people into the market each day. This vast marketing machine was still firing on all cylinders when a few of us had begun to worry that the rest of the country was about to look like Seattle.

Based on three days of data from one market, I wrote a report, my first in years. We published it at 5:08 a.m. on Wednesday, March 4. It said that pending sales had just hit a two-year high, but “over the past three days in Seattle, where the first U.S. coronavirus death was confirmed… we’ve seen a significant drop in demand from homebuyers and sellers.” We emailed it to all our customers. One customer replied asking me to apologize personally to everyone who had hired Redfin to sell a home. The next day, our stock started falling.

March 12, Video Tours: “We’re Gonna Need It and It’s Gonna Work”

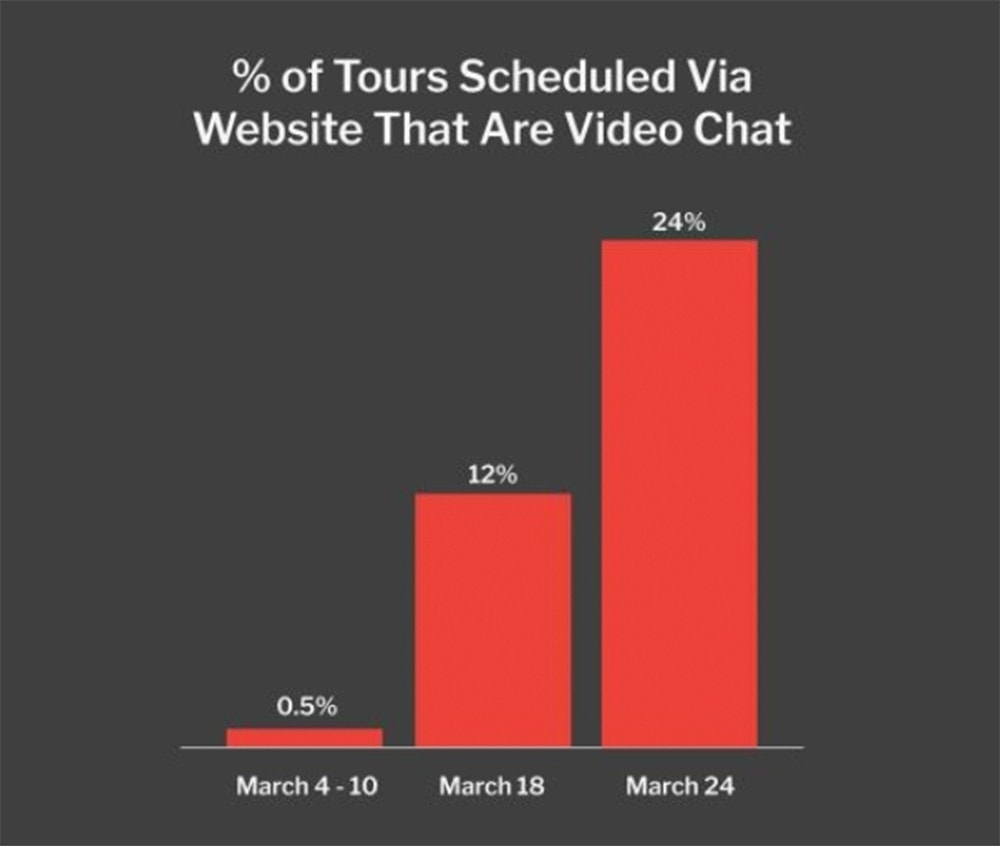

First in Seattle, then across the country, commerce came to a halt. We canceled all open houses. We limited in-person tours. Before that happened, a rogue San Francisco engineering team had posted a notice on our website encouraging customers to tour homes via video chat. That was on Tuesday, March 3. But only .5% of the customers who asked us to host home tours did so. The engineering team still wanted to develop a much more serious capability.

I was skeptical. I’d been an enthusiast for video-chat tours years before, and the team that had launched it back then had mostly quit because nobody wanted it. That experience had convinced me that people needed to see houses in person to be able to buy them. We spent a few precious days arguing about video-chat tours. The breaking point was on Thursday, March 12, when I asked an executive, Christian Taubman, if one of our software-development managers was excited about coding it. Christian shot back:

I don’t know what **** thinks. I believe in it. It’s important that we make a decision on this and move on. I believe in it, I think we should do it, and I’m willing to be accountable for it. We’re gonna need it and it’s gonna work.

That last line was what did it; it felt like the first statement of certainty we’d heard in days. Two weeks later, our demand would be about half of what it was before the pandemic, but nearly one in four online tour requests asked for video-chat.

We would soon be writing contracts for buyers and sellers to agree on a price before letting the buyer enter the empty home for her first in-person visit. And I was on CNN, talking about all of it like it was my idea.

March 13: The Circuit-Breakers Flip, an Investor Comes Calling

The next day, I was riding my bicycle toward a now-empty office when my phone rang. It was Henry Ellenbogen, who had first invested in Redfin in 2013, when we were still private. He had recently started a new fund, Durable Capital. He asked about life in Seattle, and then how many people were in the aisles of my Safeway; conversations with him were often like that, seemingly idle and then pointed. Henry was calculating which parts of the economy would stay open when the rest of the country looked like Seattle.

I’d stopped on the street in front of our office, which was usually so busy that cars had to wait for several turns of the same stop-light to get through. “You could take a nap on this street now,” I told Henry.

As a rule, I don’t check Redfin’s daily stock price, but Henry’s call made me wonder if it was now falling fast. It had been at $32 on February 21; by March 18 it would reach $10. Henry wanted to know if we needed more money. He said he could buy our stock on the open market instead of directly from us, but then investors would get his money, not Redfin. I didn’t respond. He probably knew we’d say nothing and then we’d say yes.

Back in December, Henry explained to me that he couldn’t beat the algorithms that have replaced most human stock pickers; the exception was during a time of chaos, when the computer models break down. Now, while we were on the phone in March, Henry observed that the stock-exchange circuit breakers had just flipped, putting a temporary halt to a computer-driven market free-fall. Chaos.

Yet he was in no hurry. “Tell me something,” he said. “When people start touring homes via an iPhone, won’t a lot of them decide, even after this whole pandemic ends, that this is just a better way to see houses? And if this whole process of buying and selling homes mostly goes virtual, how will other brokerages compete with you?”

“I don’t know Henry,” I said absently, peering into a darkened restaurant.

“Well I do,” Henry said. “The world is changing in your favor.” He told me to let him know if we needed his money. I still thought we wouldn’t: we’d started the year with $336 million in the bank, with a plan to add millions more along the way. And I knew that deals have their own momentum: as soon as you tell anyone you’re considering a deal, the deal almost becomes inevitable. I hung up resolving to keep Henry’s offer to myself for a few hours.

It took me a minute to wheel my bike around the back of the building, but then I paused before descending into a garage without cell service. I called Chris Nielsen, our CFO. Chris was quiet, but firm: we would have to consider Henry’s overture. I started to grouse that any deal in a distressed market would be set up to punish us if Redfin didn’t recover. And Chris said that’s exactly why we had to consider taking it: “If Redfin is slow to recover, we’ll need every penny.”

Chris told me that every company in America with a revolving line of credit was drawing down as much cash as it could, in case its lenders failed, or found a way to say no. In the month of March, this amount would exceed $200 billion in a “revolver frenzy.” We didn’t have a line to more money. Chris had already modeled every way we could get into and out of a jam. There were a lot of ways in, and only a few out.

We would later call the capital-markets desk at a big bank, and learned that trillions in global capital were already lining up to buy into the carnage. Our chairman, Bob Mylod, would put together the head-spinningly intricate terms of an acceptable deal on a phone call with Henry. An army of Wall Street analysts, who weren’t exactly eager to endorse a deal we had found on our own, spent a weekend determining that the terms were fair. It was as if Bob had calculated in his head the fuel needed to send a spaceship to the moon, and guessed exactly right.

At a time of bad deals, it was a good one. By Friday, March 27, I would get bent out of shape on a call with our board about whether to increase the deal size from $100 million to $110 million. I hated the Silicon Valley habit of raising and losing so much money, and we already had enough in reserve to get through one year of hell. But the board wanted enough for two.

By the time I talked to Bob about it that Sunday, my head had cleared. While we were on the phone, Bob mentioned that the futures market had opened, predicting huge losses on Monday. “ABC,” Bob said, hanging up. “Always be closing.” He liked to quote a line like that from David Mamet, or Shakespeare, or Bill Murray in Caddyshack; then, when his point seemed too serious, he would chuckle. But it hit home. The board approved the final deal terms that night. Our legal team worked into the wee hours to lock in the price, getting the deal done before trading opened on Monday, March 30.

End of part one! Tomorrow: Sell, Sell, Sell.

Feature photo by chaddavis.photography (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

United States

United States Canada

Canada